A Community of Archaeologists

In a quiet village in Norfolk, England, a group of archaeologists and volunteers are exploring the past. They are part of the Sedgeford Historical and Archaeological Research Project (Sharp), a community-based field research project aiming to uncover the full history of the community from the Stone Age to the First World War. The project was founded in 1996 by Neil Faulkner, an archaeologist and writer who died in 2022. He wanted to create a democratic and inclusive approach to archeology where everyone can participate and learn.“Sharp is an exercise in democratic archaeology,” Faulkner told the Guardian in 2017.“Everyone involved, from seasoned professionals to amateur volunteers, work together as one team. We share our knowledge, skills and enthusiasm and learn from each other.

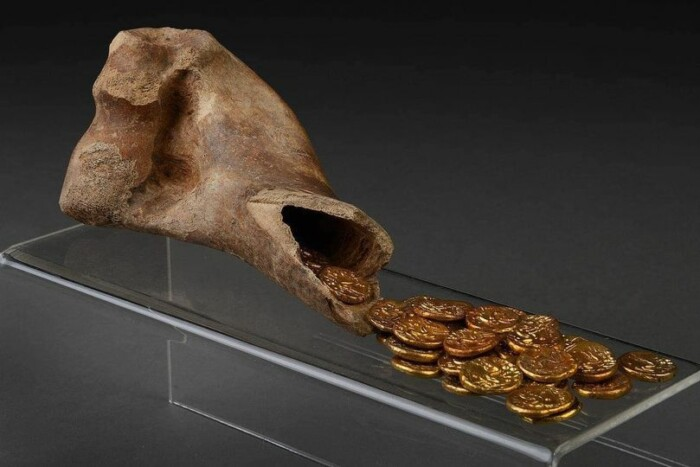

Projecthas made many fascinating discoveries over the years, such as a large kiln complex for drying malt, a key ingredient in brewing, dating back to around 800 AD. They also found evidence of burials, metalworking, pottery and animal husbandry from different historical periods. But one find stands out as the most unusual and mysterious of all: a hoard of 32 Iron Age gold coins buried in the bone of a cow.

A Hidden Treasure

The treasure was discovered in 2003 in a ditch near an ancient trail used by travelers for centuries. The coins were hidden in cow bone, open at one end, filled with gold, and then sealed with clay. The bone was then wrapped in cloth and placed in a stone-lined pit. Who buried this treasure and why? And how did they get such valuable coins?coins are gold and weigh approximately 6 grams each. They are approximately 18mm in diameter and approximately 2mm thick. They are beautifully and precisely crafted, with intricate designs on both sides. On one side they show a stylized head, possibly representing a Celtic god or sun and healing goddess like Apollo or Belenos. On the other hand, they represent a horse, which can symbolize strength and agility or an affinity with warriors and rulers.

Thecoins are of the so-called E-Gallo-Belgian type, minted between 60 and 50 BC. BC by Celtic tribes in northern France and Belgium. They were based on an earlier type of coin called Gallo-Belgique A, an imitation of the Greek coins of Massalia (now Marseille). Gallo-Belgian e-coins were widespread in Britain before the Roman conquest, particularly in southern and eastern England. They could be used as currency or as gifts or offerings.

“These coins are very rare,” said Gary Rossin, one of the Sharp executives involved in the find.“I’m not Norfolk; comes from overseas. They show that there was a lot of exchange and contact between Britain and continental Europe at the time.

”Thehoard is one of the largest and most important Iron Age coin finds in Norfolk. It shows that the region was part of a complex trade and exchange network linking Britain to mainland Europe. It also indicates that the people who lived there had access to wealth and prestige that reflected their status and identity.

The treasure may have been buried for safekeeping or as a ritual deposit during political or social unrest.

“We don’t know why they buried him,” Rossin said. “Maybe it was for security reasons, or maybe it was a votive offering to the gods. Maybe they were afraid of the Romans coming, or maybe they were celebrating something.”

The hoard is also a challenge for the archaeologists who study it. They have to use various methods and techniques to analyze and interpret it, such as metal analysis, radiocarbon dating, coin identification and historical research.

A Clue to the Past

The hoard is a clue to the past, but also a mystery that remains unsolved. Who buried it and when? What was their story? What happened to them? And why did they choose to hide their treasure in a cow bone? These are questions that may never be answered, but they invite us to imagine and wonder about the lives of our ancestors.

“The cow bone is very intriguing,” said Rossin. “It could have been used as a container or a ritual object. Maybe it had some symbolic meaning for them. Maybe it was related to their beliefs or their identity.”

“It’s like solving a puzzle,” said Rossin. “We have to put together different pieces of evidence and try to make sense of them. We have to be careful and rigorous, but also creative and imaginative.”

Conclusion

The Sedgeford hoard is an example of how archaeology can reveal hidden aspects of the past. It shows how community-based projects can involve people from different backgrounds and interests in exploring their local heritage. It also illustrates how coins can provide insights into the economic, social and cultural history of ancient societies.

“It’s a very exciting and rewarding project,” said Rossin. “We are learning a lot about the past, but we are also having fun and making friends. We are very lucky to have found this hoard, and we hope to share it with the public and the future generations.”