For centuries, humans have been captivated by the mysteries of the cosmos, and this fascination has inspired countless attempts to understand the universe’s secrets. Although there have been models explaining the cosmos for centuries, the field of cosmology is relatively new, and it involves using quantitative methods to gain insights into the universe’s structure and evolution. The foundation for this field was laid in the early 20th century with Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which is the basis for the standard model of cosmology.

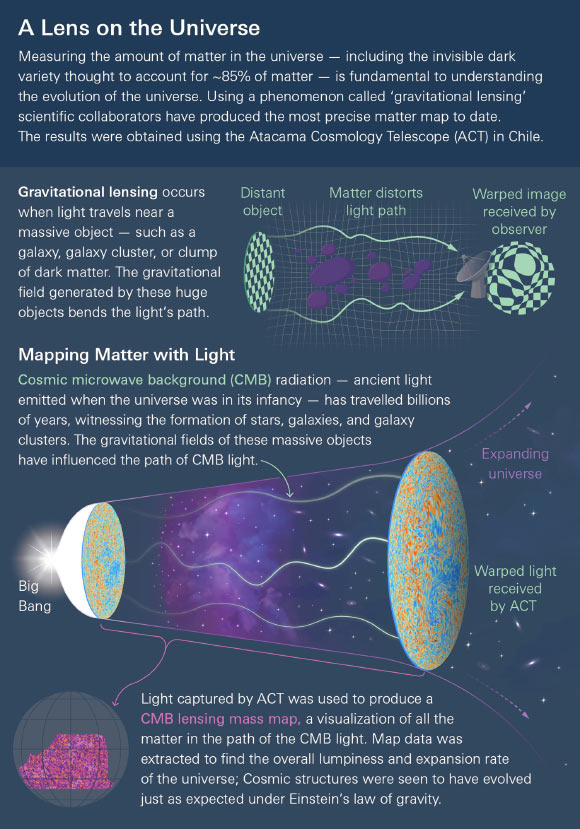

Recently, a group of researchers from the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) collaboration published a set of papers in The Astrophysical Journal, revealing an image that displays the most detailed map of matter distributed across a quarter of the sky, delving deep into the cosmos. The image confirms Einstein’s theory about the growth of massive structures and how they bend light. It is a test that spans the age of the universe, and the measurements show that both the “lumpiness” of the universe and its growth rate after 14 billion years align with the standard model of cosmology based on Einstein’s theory of gravity.

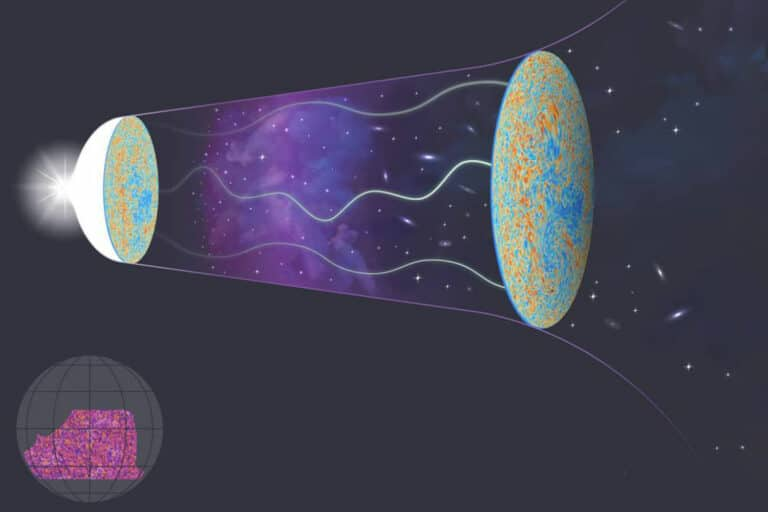

Mathew Madhavacheril, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania and the lead author of one of the papers, stated that the new mass map was created using distortions of light remaining from the Big Bang.

The authors of the papers also mention that the uneven distribution of dark matter throughout the universe is responsible for the “lumpiness” quality observed in the new mass map, and that the growth of dark matter is consistent with previous predictions. Despite its significant influence on the universe’s evolution and accounting for 85% of its mass, dark matter has been challenging to detect because it only interacts with gravity and not with light or other forms of electromagnetic radiation.

To track down the elusive dark matter, the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) was built by Penn and Princeton University with funding from the National Science Foundation in 2007. More than 160 collaborators have built and gathered data from the ACT, which is located in the high Chilean Andes. The telescope observes light that emanated from the Big Bang, the dawn of the universe’s formation when it was only 380,000 years old. This diffuse light, which fills the entire universe, is known as cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) and is often referred to by cosmologists as the “baby picture of the universe.”

The team uses the ACT to track how the gravitational pull of large, heavy structures, including dark matter warps the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) during its 14-billion-year journey to us, much like how a magnifying glass bends light as it passes through its lens.

Mark Devlin, the Reese Flower Professor of Astronomy at Penn and the deputy director of ACT, says that when the experiment was proposed in 2003, they had no idea how much information could be extracted from the telescope. He credits the success of the experiment to the cleverness of the theorists, the people who built new instruments to make the telescope more sensitive, and the new analysis techniques developed by the team.

Gary Bernstein and Bhuvnesh Jain, both researchers at Penn, have led research on mapping dark matter using visible light emitted from nearby galaxies, as opposed to the CMB. Their findings indicate that matter is slightly less lumpy than what the simplest theory predicts. However, Mark Devlin and Mathew Madhavacheril’s work on the CMB confirms the theory.

The results from ACT’s dark matter maps have narrowed down the times and places where the simplest theory could be going wrong, according to Bernstein. One possibility is that a new feature of gravity or dark energy is appearing in the last few billion years, after the era that ACT measured.

Although ACT has been decommissioned as of September 2022, more papers with results from the final set of observations are expected to be submitted soon. The Simons Observatory will continue to conduct future observations at the same site, with a new telescope that will be capable of mapping the sky almost 10 times faster than ACT, starting in 2024.