The plan will keep Voyager 2’s science instruments turned on a few years longer than previously anticipated, enabling yet more revelations from interstellar space.

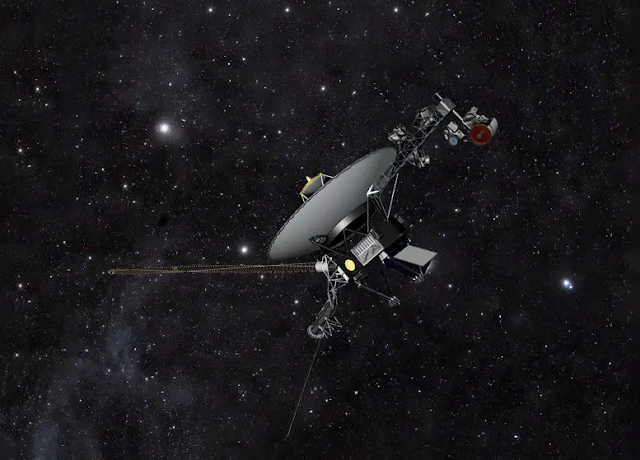

Launched in 1977, the Travel 2 spacecraft is more than 12 billion miles (20 billion km) from Earth, using five scientific instruments to study interstellar space. To help keep these devices running despite a dwindling power supply, the aging spacecraft began using a small, separately placed backup power tank as part of the onboard safety mechanism. . This decision will allow the mission to postpone the closure of the scientific instrument until 2026, instead of this year.

Turning off a scientific device will not end the mission. After shutting down the single instrument in 2026, the probe will continue to operate the four scientific instruments until power goes down requiring the other to be turned off. If Travel 2 remains healthy, the engineering team predicts the mission could continue for years.

Its twin Voyager 2 and Voyager 1 are the only spacecraft to operate outside the heliosphere, the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun. The probes are helping scientists answer questions about the shape of the heliosphere and its role in protecting Earth from energetic particles and other radiation found in the interstellar medium .

Project scientist Linda Spilker said: “The scientific data that Astronauts send back becomes even more valuable the farther they are from the Sun, so we are certainly interested in keeping as much scientific equipment as possible. learn to work for as long as possible”. The Southern California Laboratory, which manages the mission for NASA.

Power to the Probes

Both Voyager probes are powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs), which convert heat from decomposing plutonium into electricity. The continuous decay process means that the generator produces less energy each year. So far, the power reduction has not affected the mission’s scientific results, but to make up for the loss, engineers turned off heaters and other systems not critical to sustaining the mission’s flight. spaceship.

With those options now exhausted on Travel 2, one of the spacecraft’s five science instruments is next on their list. (Travel 1 uses a less scientific device than its twin because one fails early on in the mission. As a result, a decision on whether to turn off a device on Travel 1 won’t be made until next year.)

Seeking to avoid shutting down the Astronaut 2’s scientific equipment, the team took a closer look at a safety mechanism designed to protect the devices in the event that the spacecraft’s voltage – current – would significant changes. Since voltage fluctuations can damage equipment, Voyager is equipped with a voltage regulator that activates a backup circuit in such a case. Circuits that can access a small amount of power from the RTG are reserved for this purpose. Instead of conserving this power, the mission will now use it to keep scientific instruments running.

Although the spacecraft’s voltages are not strictly regulated accordingly, even after more than 45 years of flight, both probes’ electrical systems are relatively stable, minimizing the need for a safety net. The engineering team can also monitor the voltage and react if it fluctuates too much. If the new method works well for Travel 2, the team can implement it on Travel 1 as well.

“Variable voltages can pose a risk to the devices, but we have determined that this is a small risk and the alternative offers the part,” said Suzanne Dodd, Travel project manager at JPL. The big bonus is being able to keep the scientific instruments running for longer. . “We’ve been monitoring the spacecraft for several weeks and it looks like this new approach is working.”

The Travel Mission was originally slated to last just four years, sending two probes past Saturn and Jupiter. NASA has expanded the mission so that Voyager 2 can visit Neptune and Uranus; it remains the only spacecraft ever to encounter the Ice Giant. In 1990, NASA once again expanded the mission, this time with the aim of bringing the probes out of the heliosphere. Travel 1 reached its limit in 2012, while Travel 2 (moving more slowly and in a different direction than its twin) reached its limit in 2018.

Learn more about the mission

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), a division of Caltech in Pasadena, built and operated the Travel spacecraft. The Astronaut missions are part of NASA’s Astrophysical System Observatory, sponsored by the Diary Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington.