The researchers found an impressive ecosystem of ‘alien’ microorganisms in the radioactive Königstein mine in Germany.

In the picturesque Elbe Sandstone Mountains of southeast Germany, researchers have discovered a highly developed ecosystem of “alien” life forms in one of the most hostile environments known to man: the abandoned uranium mine.

The Königstein uranium mine dates back to the 1960s, when nuclear power was still in its infancy, and the world powers were quickly seeking to harness its capabilities.

After small amounts of uranium are found in this region, it suddenly evolved into a large uranium mining center. From its foundation in the 1960s until its closure in the 1990s, the mine produced more than 1,000 tons of uranium per year.

In the 1990s, production declined and local officials decided to flood the mine to alleviate all major environmental impacts and completely stop mining.

Decades after the mine closed, mine keepers noticed the exotic life forms that began to take root within its flooded walls. The watchmen decided to call the scientists over to investigate the problem, and what they found revealed the amazing truth of life on our planet.

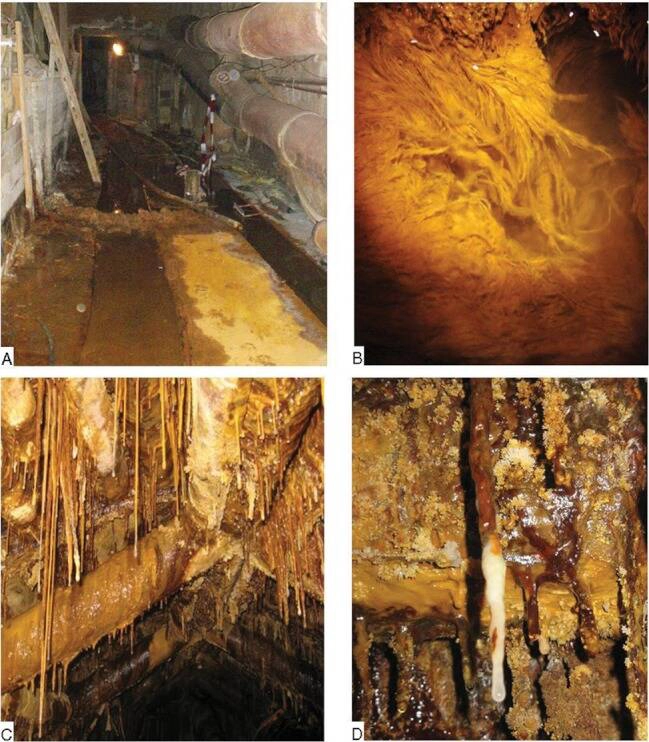

In the wet and dark beak, the researchers identified some bacteria. These acidic orange bacteria look like long worms and wall fragments. These slimy brown and white bacteria seeped out from the ceiling like stalactites.

Researchers also noted the complexity of organisms. Most are not unicellular, but multicellular, or intracellular, eukaryotes. According to Big Think, the largest of these microorganisms are 50 micrometers wide and 200 micrometers long.

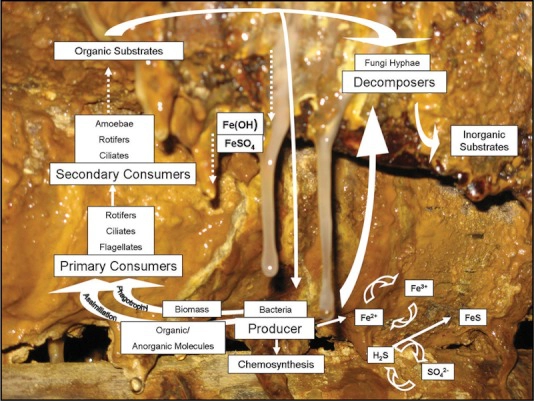

Due to the complexity of life in the mine, researchers were curious how such an impressive ecosystem could exist in such a sunlight-free and highly acidic environment.

According to the published findings of “alien” bacteria, the low pH of the beak, the high concentration of sulfates and the high concentration of heavy metals allowed the bacteria to thrive.

Many organisms are acid-loving bacteria, meaning they produce energy by ingesting the rich iron and sulfur stores of their bills. These bacteria formed a mucus-lined structure that hung from the wall of the beak.

Then, tiny eukaryotes eat the acid-loving bacteria. In turn, eukaryotes are about to be consumed by other larger organisms. This process continues, forming an organized and highly efficient food chain.

The researchers were particularly interested in the microbiome’s structured food chain and wrote in the study: “Eukaryotes colonize to a greater extent in the harsher environments than we originally thought and it is not only present but can also play a significant role in the carbon cycle at acid mine drainage communities”.

The Königstein field was not the only hostile place where researchers found complex life forms. In 2007, scientists studying Chernobyl’s reactor 4 found some fungal strains that appeared to be ingesting radiation from the site.

Even in the deepest parts of the Arctic Ocean surrounded by a vast field of hypoxic and high-pressure hydrothermal vents, scientists have found bacteria thrive.

It seems that even where we believe it to be “uninhabitable” our planet may find ways to allow life to multiply.

Scientists discovered a fungus that could “eat” radiation and grow inside the Chernobyl nuclear reactor. This particular mushroom, also known as the “radiotrophic fungi”, feeds on its own radiation and experts believe it can be used to create “sunblocks”.

It was first discovered in 1991 around and inside the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. It contains a large amount of melanin which helps it convert radiation into energy for growth.

It is particularly noted that melanin-rich fungal colonies have started to grow rapidly in the cooling waters of reactors in power plants, making them black.