A huge Viking burial hill found on the island of Karmøy off Norway’s western coast was long thought to be purge. Unearthings that opened the Salhushaugen hill in 1906 were propelled within the conviction that it held a buried Viking ship, but as it were some unremarkable artifacts were found at that time.

But a modern study by archeologists who utilized ground-penetrating radar to look more profoundly uncovered that the hill really does hold the remains of a tremendous antiquated vessel. This transport would have been built, cruised and eventually buried along side its captain at some point within the early portion of Scandinavia’s Viking Age (793—1066).

Based on different relevant clues, the long-lost dispatch shows up to have been buried at some point within the late eighth century, or actually at the starting of the Viking time of investigation and victory. On the off chance that the ship’s distinguishing proof is affirmed (and the experts are essentially certain it’ll be), this will authoritatively be the third Viking vessel uncovered from beneath a Karmøy burial hill.

Harald Fairhair , the primary lord of Norway who ruled between 872 and 930, lived in a illustrious house on Karmøy. Indeed some time recently the incredible Harald accepted the position of authority, Karmøy had long been a situate of political control in Norway, having been ceaselessly possessed by elites since the Bronze Age (back to 1,700 BC).

Since of Karmøy’s centrality to antiquated Norse society , numerous archeologists and students of history are persuaded the effective Viking culture to begin with took root on the island. Since the island is found adjoining to Norway’s western coast on the North Ocean, it would have given an perfect docking spot for approaching exchanging ships, and a culminate propelling point for Viking vessels as well.

“Usually a really vital point, where oceanic activity along the Norwegian coast was controlled,” College of Stavanger paleontologist Hakon Reiersen told Live Science .

Professor Reiersen led the team that performed the ground-penetrating radar survey, which took place at the Salhushaugen burial mound near the village of Avaldsnes. His excavations were sponsored by the Museum of Archaeology at the University of Stavanger, and represented the first deep-ground search performed at this largely forgotten site.

Penetrating History with Ground-Penetrating Radar

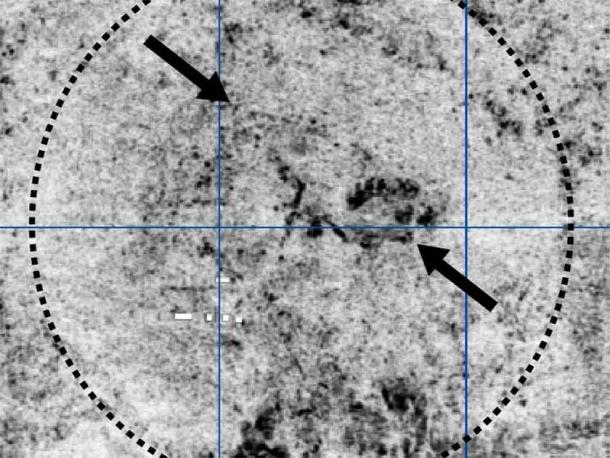

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) equipment is perfectly suited for subterranean archaeological exploration. During surveys, radio wave pulses are beamed straight into the earth, and if they strike physical objects buried beneath the ground those objects will reflect the waves back toward the surface, where they can be detected by radar. Specialists examining the radar images can determine the exact shapes of the buried objects, which can then be displayed as three-dimensional computer-generated models.

In this case, the archaeologists had no reason to suspect they’d detect anything significant at the Salhushaugen mound. But GPR is capable of finding objects buried up to 100 feet (30 meters) beneath the earth’s surface, which is deeper than archaeologists were able to dig back in 1906. And down at those greater depths, the GPR images revealed the unmistakable shape of a 65-foot (15-meter) wooden ship, apparently built in the usual Viking style.

“We’re confident this lens-shaped signal actually comes from a ship,” Reiersen said. “It shares the dimensions and size of previous ships, and it’s situated in the middle of the mound. But we don’t know how well preserved it is.”

The newly discovered Salhushaugen ship is somewhat larger than a wooden Viking ship unearthed at Karmoy´s Gronhaug burial mound in the early 20th century. But it is a bit smaller than the 65-foot (20 meter) vessel found beneath the nearby Storhaug mound, which was excavated in 1886.

Excited by this fascinating discovery, the archaeological team from the University of Stavanger plans to begin physical excavations at the Salhushaugen mound later in 2023. If the process goes smoothly, they may ultimately excavate the ship, although that is not certain (it won’t happen if they determine the process will damage the Viking vessel).

Technology Reveals the Hidden Truth at Salhushaugen

It was over a hundred years ago that archaeologist Haakon Shetelig first carried out an extensive survey of the island of Karmøy, digging up multiple burial mounds in search of Viking treasures .

Before opening up the Salhushaugen mound in 1906, Shetelig had already unearthed the ship buried in the Gronhaug mound. Shetelig was also responsible for the discovery of the famous Oseberg ship, which was buried in 834 in the southeastern part of Norway. That ship was the largest Viking vessel ever discovered, and Shetelig was hoping to find something similar when he began excavating the impressively sized Salhushaugen mound.

But his hopes were soon dashed. Despite digging down many meters, he and his team only uncovered a collection of arrowheads and 15 wooden spades, and no sign of any Viking ship.

“He was incredibly disappointed, and nothing more was done with this mound,” Reiersen said in an interview with Science Norway .

But it seems that Shetelig’s mistake is that he didn’t dig deeply enough into the mound to find what was there at its greatest depths. The problem was that he and his team struck a rock layer at the bottom of the mound, and at that point stopped their digging after concluding that there was nothing more left to be discovered.

What he didn’t realize is that the Vikings would sometimes bury their ships in rock layers. They would chip out a cavern in the bedrock, lower the ship into it, and then cover the hole back up to make sure the vessel was safely entombed.

If not for ground-penetrating radar, the archaeological community would have continued to believe that the Salhushaugen mound was both shallow and empty.

Viking Kings as the Representatives of the Gods

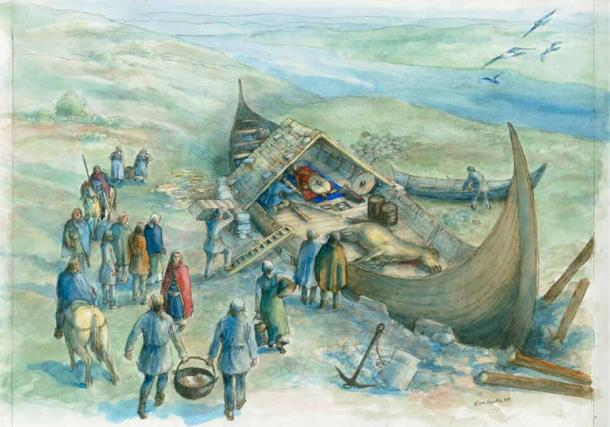

When the burial mounds were first built, they could have been easily seen by ships entering and exiting the Karmsund Strait, which separated Karmøy from Norway’s mainland. Evidence has emerged that the ship burials of Viking kings and chieftains were meant to be observed from water, presumably by other Viking captains on board their vessels. It was an incredible honor for a Viking leader to be buried inside the ship he once commanded, and naturally the ceremony would have been well-attended by other ship captains who hoped to be honored in the same way when they died.

It was the Viking custom to build their ship burial mounds in clusters, as was the case at Karmøy. Once they’d found a location that was easily observable from the sea, it would make sense to reuse those sites for burial ceremonies of important people.

According to Jan Bill, a University of Oslo archaeologist who curates the Viking Ship Collection at his university’s Museum of Cultural History, Viking funeral ceremonies like these were meant to send the buried king or chieftain off to the land of the dead. His burial with his ship was symbolic, as it was meant to represent the long journey he was about to undertake sailing through the spirit world.

“I think these ship burials go back to a way of consolidating power among Germanic peoples,” Bill said. “The idea was that the king was a descendant of a god, such as Odin or Wotan.”

The ship burial ceremony would have reinforced this identification, as this type of honor was reserved strictly for Viking elites of exalted status. This linking of Viking leaders with Norse gods would have given a supernatural sanction to all of their actions, which would have helped unify early Viking culture by sending the message that their kings were divine messengers who could do no wrong.

Source: Museum of Archaeology, University of Stavanger/ Science Norway